When treating our medical dermatology patients, beyond the objective—whether it’s an investigator’s global assessment (IGA), a lesion count, or a PASI score—it’s important to also understand the type of reaction patients are having, the fears they’re having, the hopes they’re having, and their motivations. Patients have different emotional responses to the conditions that they come to us to have treated. Many times people have identifiable emotional reactions. They’re anxious. They’re angry. They’re frightened. They’re depressed. But it doesn’t always manifest in the classic ways. Very often the anxiety that comes with skin disease is more a free-floating feeling of discomfort—a little bit of tightness in the chest or a generalized jitteriness and apprehensiveness. Frequently it manifests as some social anxiety and avoidance of social activities and people. These patients may feel as though they have lost some spark and motivation in their lives. In order to engage with patients and ensure that your treatment plan works for them, assessing and understanding their fears, motivation, and hopes is key.Fear.

When treating our medical dermatology patients, beyond the objective—whether it’s an investigator’s global assessment (IGA), a lesion count, or a PASI score—it’s important to also understand the type of reaction patients are having, the fears they’re having, the hopes they’re having, and their motivations. Patients have different emotional responses to the conditions that they come to us to have treated. Many times people have identifiable emotional reactions. They’re anxious. They’re angry. They’re frightened. They’re depressed. But it doesn’t always manifest in the classic ways. Very often the anxiety that comes with skin disease is more a free-floating feeling of discomfort—a little bit of tightness in the chest or a generalized jitteriness and apprehensiveness. Frequently it manifests as some social anxiety and avoidance of social activities and people. These patients may feel as though they have lost some spark and motivation in their lives. In order to engage with patients and ensure that your treatment plan works for them, assessing and understanding their fears, motivation, and hopes is key.Fear. Often the greatest fears patients have regarding skin problems are that it’s going to escalate in intensity and body areas involved, that it will never go away, or that it will become more and more unpredictable and volatile.

Motivation. It’s often assumed that when a patient presents to us with eczema, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, that s/he

wants to be there. Clinically many of us have gotten used to not being so certain about that with the adolescent—is this mom or dad’s issue? Sometimes patients of any age have ambivalent motivation or minimal motivation to do the work that needs to be done to get better. Find out what they are motivated to achieve from treatment.

Hope. What is their hope or expectation? What is their threshold to have some improvement in how they feel and how they function? For some people it is a 10 percent reduction in itch or to clear the visible lesions in the most commonly exposed areas.

To determine these factors, it’s not necessary to spend 45 minutes or an entire appointment discussing psychological issues. But it should be a quick part of our initial examination. Ask patients directly how bothered they are. Ask them if they’re motivated to be there. Then give them a sense that we take their complaints and their skin problems very, very seriously, and validate their feelings of anxiety, frustration, and skepticism (if present).

Start by asking, “How bothered are you by your condition?” If someone says, “It bothers me tremendously. It’s on my mind all the time. It’s keeping me from doing so many of the things I want to do,” it’s right out there. If the answer is, “Whatever, it never bothers me,” that deserves a second pass. Sustain eye contact for two to three seconds and ask, “Honestly, is it tough to live with this?” Nine times out of 10, holding eye contact for just two or three seconds will result in a much more honest forthcoming statement of either yes or no.

Beyond verbal responses, observe how patients act. If there is no visible affect, no eye contact, no smile, and, blunt affect, this is someone who is exhibiting warning signs that s/he might be profoundly depressed. I want to know from this person, “Tell me something. Is today just a tough day or are you going through a difficult time? You seem awfully sad.” This doesn’t need to become a psychotherapy visit, but it should at least be included in our assessment of the patient and perhaps be reason to offer referral for therapeutic support.

Next, ask patients, “Who’s idea was it to come here?” If they say it is their own, great. But if it was a spouse’s or parent’s idea, follow up and ask if that’s OK with them. Through years of experience treating adolescents, I often say, “There’s actually only one true boss in this room when it comes to your skin. It’s not me. It’s not your mom. It’s not your dad. It’s you. So if this is something you’re motivated to improve, I’m in there with you. If it’s something that you don’t want to bother with, I’m well aware of the fact that I can give you some great ideas and you’re going to look at me, smile, and nod and then go home and do nothing. So tell me something, is it important to you? If it is, it’s important to me.”

In a nut shell: Offer the patient the control they need.

Look for signs that the skin problem is causing patients “pain.” We often underestimate how uncomfortable skin disease can be. Acne can hurt. Psoriasis can hurt and itch. Eczema can itch and sometimes hurt. With rosacea, often the skin feels hypersensitive. Ask, “Does your skin condition make you feel uncomfortable?” If the answer is, “Well, this makes my skin feel uncomfortable, but not me,” the patient is telling you that s/he is pretty okay emotionally. If the patient says, “It makes me feel incredibly uncomfortable,” ask a follow-up question. “Do you mean it itches, tingles, hurts, burns, and it makes you feel uncomfortable in your skin?” Usually patients will answer yes to both. Then my answer is, “I take that very seriously and I want to make both you and your skin feel more comfortable.”

Determine if your patients are confused or overwhelmed when they come to your office. They may have looked their condition up online and have already tried “miracle” cures they’ve found there. Our patients’ heads are often so filled with contradictory, confusing information that they’re overwhelmed. Often, they have already tried natural remedies by the time we see them and have been repeatedly disappointed. They are justifiably skeptical and mistrust what we’re offering.

To combat this, I often say to patients, “We take your [acne, rosacea, psoriasis, eczema] condition very, very seriously and we have terrific tools to improve it, but you have every right to be like somebody from Missouri.” I go on to explain that Missouri is the “Show Me” state and that it is totally understandable if they are skeptical and doubtful until I can demonstrate to them and show them that we really do have effective therapies that will help improve their skin condition. We need to validate that patients have a right to ask us to prove ourselves and not be yet another person in line who’s giving them false hope.

Understanding patients’ motivations and expectations can help direct our treatment regimens and recommendations. We need to walk the line between over-promising and under-promising. The last thing a patient wants to hear is that it is going to take a long time for treatment to work. I try to help patients focus on the visible signs that indicate the skin is responding. With an acne patient, I explain, “By the time you see a new pimple come out, it started forming about three weeks ago under the skin. So even if this pill I give you today stops all new pimples from forming, you’re still going to have another couple of weeks of acne that’s already formed. However, the medicine that I’m giving you should start to act reasonably quickly by minimizing how big the pimple will get and helping it to melt away more quickly. So, yes, you’re going to see some effect very quickly.”

If it’s psoriasis or eczema, I’ll say, “Look, the reason you have these conditions is because you have an immune system that works too well. In fact, it works so well, it is so ready to do business, it so full of vim and vigor that it can’t control itself. When the immune system functions as it should, it should essentially be the police officer in the skin. What’s the job of the police officer? To look for the bad guys. What are the bad guys of the skin? Bacteria, fungus, virus, and cancer. We’ve got cells that God or nature has given us that are essentially those police officers, on guard and vigilant for infectious or neoplastic processes. What happens with eczema and psoriasis and acne and rosacea, is the immune system overreacts in the skin as if there is a bad guy in or on the skin. When it overreacts, it releases chemicals that can make the skin red, bumpy, blotchy. It can itch. It can tingle. It can hurt. It can burn. The treatments I’m going to give you won’t necessarily totally clear your rash very quickly, but within a couple of days you’ll notice that the skin looks less intensely red. You can see that it might be scaling less. It will start feeling better. There are going to be indicators that the immune cells are starting to understand that really they don’t have to get so angry.”

This approach lets patients know that I take them and their need for early signs of efficacy very seriously, that I appreciate that their skin problem is a big deal. It also implies that we have a shared responsibility. I’m offering a 20 second explanation that their genes and immune system play a role and that we can work together as a team to help get the skin and immune system to behave better.

Empower patients that they are in the driver’s seat and that they need to speak up if something with their treatment regimen isn’t working. I tell patients, “Look, this is what I’m going to recommend you do but I want to make sure I stay within the ‘Rules of Treatment’ and my rules of treatment are that anything I give you should be quick and simple, nobody else should know you’re doing it, and it should work. If I violate any of those rules, call me. If you don’t like the way something feels, the way it looks, the way it smells, or what it’s doing, call me because I don’t want you to come back here in three, four, or six weeks and say you stopped the treatment. You just gave up six weeks of time that we could have been getting you better.”

We have to have that open-minded communication. And we have to keep treatment simple, so patients can easily follow the regimen. Rather than following the KISS acronym (Keep it Simple and Stupid), I prefer KISE (Keep it Simple and Elegant). Give patients the control to know that they can reach out at any time to the office.

Read More:

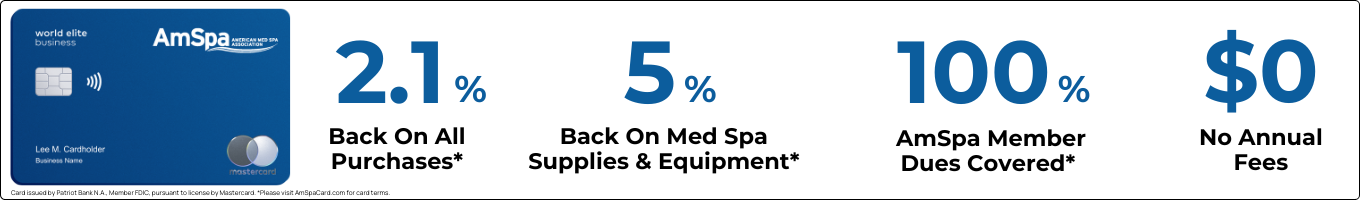

Practical Dermatology  Register Today! How to Successfully Open a Medical Spa--Northwest: September 19-20, 2016How to Successfully Open a Medical Spa--Texas: November 6-7, 2016Southwest Medical Spa Regulatory Workshop: December 5, 2016

Register Today! How to Successfully Open a Medical Spa--Northwest: September 19-20, 2016How to Successfully Open a Medical Spa--Texas: November 6-7, 2016Southwest Medical Spa Regulatory Workshop: December 5, 2016

W

W