Legal

HB 3749, Greg Abbott, and... John Oliver?

HBO's Last Week Tonight with John Oliver discussed public concerns about how med spas operate.By Alex Thiersch, CEO, AmSpaJohn Oliver ...

Posted By Madilyn Moeller, Tuesday, February 22, 2022

By Michael Meyer, Writer/Editor, American Med Spa Association

The treatments provided by lasers and other energy-based devices have always been among the signature offerings in medical aesthetics. They are versatile, are generally quite safe, and provide satisfying, visible results. Today, laser and energy-based treatments trail only injectables in terms of popularity in medical aesthetics, and numerous practices do exceptional business offering them exclusively.

But how do energy-based devices work, and why are they so well-suited for aesthetics? Here's a quick look at the past, present and future of laser and energy-based devices in medical aesthetics.

"Laser" is an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation," and the theoretical foundation for this technology was pioneered in the early 20th century by the likes of Max Planck, who discovered that energy can be only emitted or absorbed in distinct portions, which he called "quanta;" and Albert Einstein, who proposed the concept of the stimulated emission of excited atoms and molecules, which would lead to nearly a half-century of research and development before the first functional energy-emitting devices were developed.

The initial product of this research was not the laser, but the "maser"—"microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation"—which was introduced in 1954. The maser did project energy (the original model stimulated ammonia molecules), but at relatively low frequencies. As development on maser technology continued, scientists began using different substances to create higher-frequency projections until, in 1960, physicist Theodore H. Maiman created a maser-like device that projected high-frequency energy on visible spectra using ruby. This was the world's first laser.

It didn't take long for dermatologists to begin using lasers for medical purposes. In 1963, dermatologist Leon Goldman, MD, began to use lasers in his practice. Goldman began researching lasers almost as soon as they were introduced, studying their utility for procedures such as hair removal, tattoo removal and the treatment of vascular malformations—procedures with which the use of lasers are still widely associated today. (For more about Dr. Goldman, see the profile on page 16.)

In 1980, a pair of American scientists—R. Rox Anderson, MD, and John Parrish, MD—discovered that using specific wavelengths in laser treatments helps destroy specific molecules, which allowed scientists to develop laser treatments that could better target specific issues without harming surrounding tissue as severely as before.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began issuing guidelines for the use of lasers in dermatological contexts in 1984, which helped to legitimize the practice. The administration now updates these guidelines every year.

In 1992, another energy-based technology, intense pulsed light (IPL), was pioneered primarily to treat vascular lesions without causing purpura, a somewhat common issue that laser treatments can produce. IPL uses a broad spectrum of light delivered in pulses; certain wavelengths can be filtered out to prevent unwanted results but effectively treat the patient's issue. IPL devices provide less concentrated power than lasers and are less precise, but they are much more versatile—an experienced IPL technician can treat numerous conditions using a single device and can even address multiple types of discoloration in a single treatment, making it ideal for skin rejuvenation.

In 2009, R. Rox Anderson, MD—one of the same scientists who discovered that different laser wavelengths affect different molecules in 1980—and Dieter Manstein, MD, pioneered an energy-based procedure called cryolipolysis, which, put simply, destroys fat by freezing it. The following year, it was approved by the FDA for use on "love handles," and it subsequently has been approved for use on other areas. This procedure is generally known by its most recognized trade name, "CoolSculpting." Similar procedures use heat from lasers, radio frequency, ultrasound or even electrical stimulation to non-invasively "melt" fat; "Emsculpt" and "SculpSure" are among the products that use this technology.

In recent years, much of the research involving aesthetic applications of lasers has been dedicated to refining their use to provide more precise, less painful patient experiences.

"Lasers now seem very easy to use," says Terri Wojak, LE, owner of Aesthetics Exposed Education and author of Aesthetics Exposed: Mastering Skin Care in a Medical Setting and Beyond. "Some will actually choose the settings for you. They have very high-tech interfaces that make them pretty foolproof. It makes it difficult to pick the wrong settings to start out with."

However, despite the relative simplicity of laser treatments, proper training and supervision are still vital.

"It's still scary to do lasers with people who are not trained properly," Wojak says. "Regardless of how easy the interfaces look—it seems like you would just be able to press the buttons and then go on and do your treatment—the practitioner needs to know why those settings are being chosen. They need to have that background of what lasers do, how they interact with the skin and why they're choosing the settings they do, so they don't harm any patients. You can burn somebody very easily if the treatment isn't done properly."

But bad outcomes are the exception with energy-based treatments, not the rule, and they remain hugely popular. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' (ASPS) 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report, there were 997,245 laser skin resurfacing treatments, 827,409 IPL treatments and 757,808 laser hair removal treatments administered in the U.S. in 2020. (Of course, the 2020 numbers were greatly affected by COVID-related shutdowns and social directives—the ASPS survey revealed a 16% decline from 2019 across all cosmetic minimally invasive procedures, after years of steady increases.) In fact, laser skin resurfacing trailed only botulinum toxin type A (Botox, Dysport, Xeomin, etc.) and soft-tissue filler injections in terms of frequency, and IPL and laser hair removal trailed only those two types of treatment and chemical peels.

The use of energy-based devices in medical aesthetics shows no sign of slowing down. In fact, the key advancement coming to laser technology will open it up to numerous new potential patients and hopefully help to remove one of the technology's greatest roadblocks.

Since lasers were developed, there has been something of a stigma about laser use on people with darker skin tones. Because lasers typically operated at fixed wavelengths that were optimized for skin and hair with less melanin, they often produced unsightly scarring and white spots at treatment sites on people with darker skin, and the removal of darker hair was less effective. As lasers have grown more sophisticated, however, this has become less of a concern—particularly if the laser technician performing the treatment is aware of the issue—and soon it may be eliminated altogether.

"Some companies offer a very fast pulse width, which is basically where the energy is extremely fast," says Wojak. "It's like when you're touching a hot stove to see if it's hot—it's using the energy so fast that the color doesn't hold on to the heat. There are also ways to extend the pulse width, so that you're delivering the energy slower, so it's safer for darker skin types. The devices now have newer ways of delivering energy, but practitioners still need to use precautions when treating darker skin types. Hopefully we'll move toward more devices that actually read the skin and can determine the settings for the client, which would help with some of the safety issues."

The advancement of energy technology will help these devices treat not only a wider variety of skin types, but also numerous conditions for which they have not traditionally been suitable.

"Pico lasers are very exciting," says Wojak. "Pico lasers are fast pulse lasers. They are showing improvement for melasma, which is very hard to treat with traditional laser and IPL. They're also showing promise for acne scars."

According to Wojak, energy-based devices will play a hugely important role in the future of medical aesthetics.

"Lasers will always have a place in the industry, because they work—they are effective," she says. "They're safe when used in the right hands, with the right training and on the right clients. Energy-based devices are not going anywhere—they just continue to grow, and there are new technologies coming out all the time."

AmSpa Members receive QP every quarter. Click here to learn how to become a member and make your med spa the next aesthetic success story.

Related Tags

Medical spa news, blogs and updates sent directly to your inbox.

Legal

HBO's Last Week Tonight with John Oliver discussed public concerns about how med spas operate.By Alex Thiersch, CEO, AmSpaJohn Oliver ...

Trends

By Patrick O'Brien, JD, general counsel, and Kirstie Jackson, director of education, American Med Spa AssociationWhat is happening with glucagon-like ...

Trends

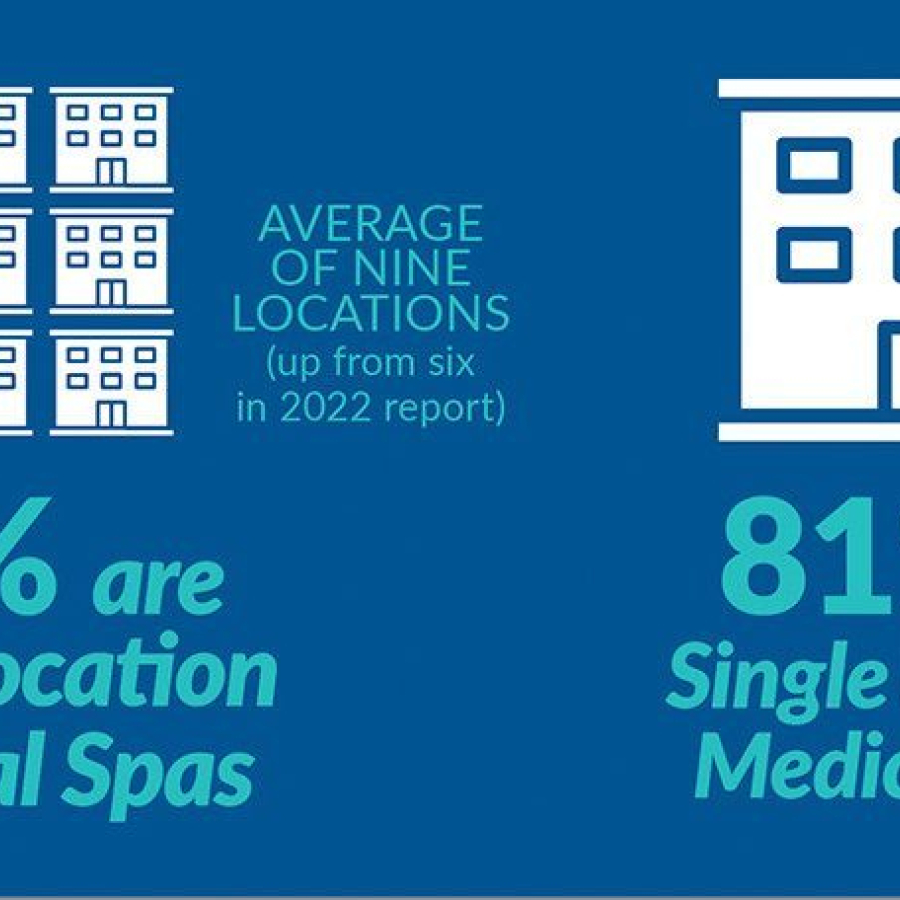

By Michael Meyer Approximately every two years, the American Med Spa Association (AmSpa) releases its Medical Spa State of ...

Trends

By Michael Meyer Since the beginning of 2024, it seems like medical aesthetics has taken one hit after another ...