Legal

HB 3749, Greg Abbott, and... John Oliver?

HBO's Last Week Tonight with John Oliver discussed public concerns about how med spas operate.By Alex Thiersch, CEO, AmSpaJohn Oliver ...

Posted By Madilyn Moeller, Thursday, March 31, 2022

By Madilyn Moeller

In medical aesthetics, interacting with patients who are concerned with their appearance is an everyday part of a provider's job. However, medical professionals might also see patients who are worryingly fixated on a particular flaw—to an extent that it negatively impacts their life. And if your providers aren't seeing them, they may not be looking hard enough.

Among cosmetic dermatology patients, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) has an incidence that may be as much as 600% higher than in the general population, according to Brito et al, 2016. In many ways, medical spa providers are uniquely poised to address this condition, but they must know how to recognize it.

To that end, implementing a cryptic screening protocol will help to open the narrative and allow body dysmorphic patients to get the care and attention they need.

Among the general population, the prevalence of BDD is between 0.7% and 2.4%, with an approximately equal incidence in females and males. In cosmetic dermatology patients, the prevalence of BDD has been measured at higher than 14%, with an incidence of three females to one male. This increased incidence in females is thought to be due to the higher proportion of female aesthetic patients—in 2020, approximately 92% of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures were performed on women, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

The average BDD patient is 34 years old, although onset of the condition may occur earlier than 18 years of age. AmSpa's 2019 Medical Spa State of the Industry Report found that 18-34 year-olds make up 24% of female medical spa patients and 18% of male medical spa patients. Also, 35-54 year-olds make up 53% of female patients and 60% of male medical spa patients.

BDD is a condition within the class of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. According to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, the condition is characterized by:

Practitioners may encounter muscle dysmorphia, a preoccupation with the idea that your body build is too small or not muscular enough, which is a form of BDD seen more frequently in male patients.

The level of insight or delusion about body dysmorphic beliefs varies from recognizing that the beliefs are definitely or probably not true to being convinced that the beliefs are true.

BDD has comorbidities with depression, mania, social phobias, substance abuse, generalized anxiety disorder, suicidal tendencies, post-traumatic stress disorder, delusional thoughts and narcissism, according to Vindigni et al, 2002. Alarmingly, BDD patients experience a high rate of suicidal ideation and attempts, with a lifetime suicide attempt rate of just over 35%, according to Pellegrini et al, 2021.

You and your staff may be able to recognize some problematic behavior in the waiting room. If a patient can't sit still or is checking their mirror or phone the whole time, they may have be overly concerned that aesthetic treatment.

Other red flags include bringing in albums of people they want to look like or things they want done, coming in with photos of themselves that are filtered or altered, showing the practitioner celebrity photographs to emulate, or coming prepared with a checklist or diagram.

Patients with body dysmorphia may have unattainable expectations when shown anticipated results in the mirror, may see no difference in the before and after photos of other patients, or may have a hard time looking at their own images.

You should also look out for patients who keep going back to one particular flaw; camouflage themselves with lots of makeup, hats and/or scarves; or obsessively look in the mirror. Watch out for patients who tell you they have been to multiple offices asking for treatment with no luck.

"If they say to you, 'I'e been to this place and that place and no one can help me, but you can,'" take note, says Leslie Fletcher, MSN, RN, AGNP-BC, of Injectability Clinic in Torrance, California. "They use a lot of passive-aggressive, borderline personality disorder traits where they're kind of buttering up and flattering the injector. That would be a red flag."

Take all of these warning signs in context; if a patient shows one behavior, it does not mean they have a medical disorder. But if they avoid their photos or bring in heavily filtered images of themselves, are obsessively mirror-checking and have been to multiple places, it's a huge red flag, Fletcher says.

After learning about the prevalence of BDD in aesthetics, Fletcher developed a cryptic screening protocol for BDD, designed not to alert patients that they are being evaluated. She coordinated with eight medical spas to screen 734 new aesthetic patients for BDD from June 1, 2019, to September 1, 2019.

The front desk staff administered the cryptic pre-screening form to all new, incoming patients between ages 18 and 65. To avoid intentionally fake answers from body dysmorphic patients (who would have been motivated to pass an official screening), the cryptic screening was disguised as a checklist of personal goals, helping providers to determine the prospective patients' psychological motivators for treatment.

Four unhealthy motivators were hidden among the 19 items, including the goals to "look perfect," "look 20 again," "look perfectly symmetrical" and "fix one particular flaw." If one of these was checked, it signified a red flag, and the injector or practitioner was prompted.

At this point, the practitioner had a conversation with the patient where the practitioner said something along the lines of, "It looks like you circled that you want to look perfect. What do you mean by that?" At that point, the fixation would often come out in verbal dialogue, or the practitioner would spot a benign motivation.

The patient was then given the secondary screening, which was a modified Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire (COPS) for BDD. This asked the patient to describe their features of biggest concern, rank them by priority, and assess the impact of those concerns on their daily life.

Fletcher's study found a BDD prevalence of 4.2% among these new patients, 29% of whom screened positive for BDD after the modified COPS screening. Practitioners refused to treat 77.8% of those positive screenings; the remainder were screened a third time and treated with positive results.

Body dysmorphic patients were referred to three mental health professionals in the region with whom Fletcher had developed a relationship. Fletcher believes practitioners have a responsibility to encourage their patients to seek help.

"At the very bare minimum, just say 'I suggest you see a therapist who specializes in this,'" Fletcher says. "To give them three therapists in the area that do that is a really wise decision, I think, because it's going to make that choice easier."

How do you talk to someone after they'e failed the screenings? "That's a tough one," says Fletcher. "I think it's the most challenging part of it. You'e got all this in place, but when you actually have to tell them that they'e failed, it's really tough."

Fletcher offered her script: "At Injectability, we really think it's important to check for your psychological health before we do treatments, and I'm concerned that this treatment might not be the best for you. You might be a little too concerned about this particular area, and I'm concerned that you might not be happy with treatment. Our success rate is really important to us, and I just want to make sure we can treat you successfully, and it's not looking to me like this is going to be a success."

Refusing to treat body dysmorphic patients is protocol. Fletcher suggests gently communicating this to patients.

"It's not a 'no' forever; it's a 'no' for now," she says. "The patient needs to investigate this and see if they can get healthier before they come back and maybe attempt to do this again. I don't want them to feel like I'm pushing them off and never want to see them again, but that we want to do it in a healthy way."

Why did those providers refuse to treat 77% of the patients who screened positive for BDD? There are a few reasons.

First of all, it's unlikely that these patients will be satisfied. "Nearly 98% of patients who get treatment who have body dysmorphia are not seeing any results," Fletcher says. "They claim that they didn't get any better, and even got worse, in some cases," per the review by Bowyer et al, 2016.

Medical aesthetics providers who treat body dysmorphic patients are also at increased risk for retaliation, whether it be on social media, through a bad review or with a negative response to the injector. "There are actually four documented cases of surgeons who were murdered by their patients afterwards. That's a sobering statistic," says Fletcher, citing a 2017 review by Sweiss et al.

Dysmorphic beliefs may even be worsened by aesthetic treatment. "Medical aesthetics can actually even push someone who may not have body dysmorphia to get elements of it, because now they're hyperaware of their face and look at everything in minute detail. So, aesthetics can actually encourage that a little bit more," hypothesizes Fletcher. That's why it's critical to stay vigilant and continue screening your patients, even those who pass the initial screening.

"You can open that conversation with, 'I know we took this when you first came to me three or four years ago, but I'm seeing that this is starting to become an obsession with you. I want to make sure you're healthy. I need to know that before I continue treatment with you.' Then offer them that screening again," says Fletcher.

Two-thirds of female medical spa patients are repeat patients, according to AmSpa's 2019 survey.

Often, medical aesthetics practices launch into extensive treatment plans without screening for the psychological health of their patients beforehand. Fletcher believes that this needs to be corrected. "I think it absolutely needs to happen, just having that conversation. I feel like that's the bare minimum," she says.

While practices routinely screen for physical health, auto-immune diseases and neuromuscular disorders, they generally skip the discussion on mental health. And that's a problem. "If you look at any cosmetic treatment, it's not medically necessary," says Fletcher. "So, if it's not medically necessary, it falls under the psychological domain, as far as treatment goes. To treat it like a medical treatment and not screen psychologically is actually doing the patient a disservice."

Medical aesthetics is rooted in the patient's perception and psychology: their desires and insecurities. "What we do is a very psychological thing, even when it's going well. They're getting more confidence in their appearance. They're feeling more comfortable with their bodies, in their faces; they're feeling more attractive. Those are all psychological outcomes."

Screening for body dysmorphia is one simple step that a medical spa can take to improve patient outcomes and prevent dissatisfaction or worsened symptoms in dysmorphic patients. How can a medical spa prosper if it doesn't care for the overall health of its patients?

"It's really all about what happens in the end—what is the final outcome? And if they're not psychologically healthy to start with, whether it's body dysmorphia or severe anxiety or appearance-related anxiety, how successful can we be in the end?" asks Fletcher.

For more about how to use the cryptic screening protocol in your practice, refer to Fletcher's published study:

Fletcher L. Development of a multiphasic, cryptic screening protocol for body dysmorphic disorder in cosmetic dermatology. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;00:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13885

AmSpa Members receive QP every quarter. Click here to learn how to become a member and make your med spa the next aesthetic success story.

Related Tags

Medical spa news, blogs and updates sent directly to your inbox.

Legal

HBO's Last Week Tonight with John Oliver discussed public concerns about how med spas operate.By Alex Thiersch, CEO, AmSpaJohn Oliver ...

Trends

By Patrick O'Brien, JD, general counsel, and Kirstie Jackson, director of education, American Med Spa AssociationWhat is happening with glucagon-like ...

Trends

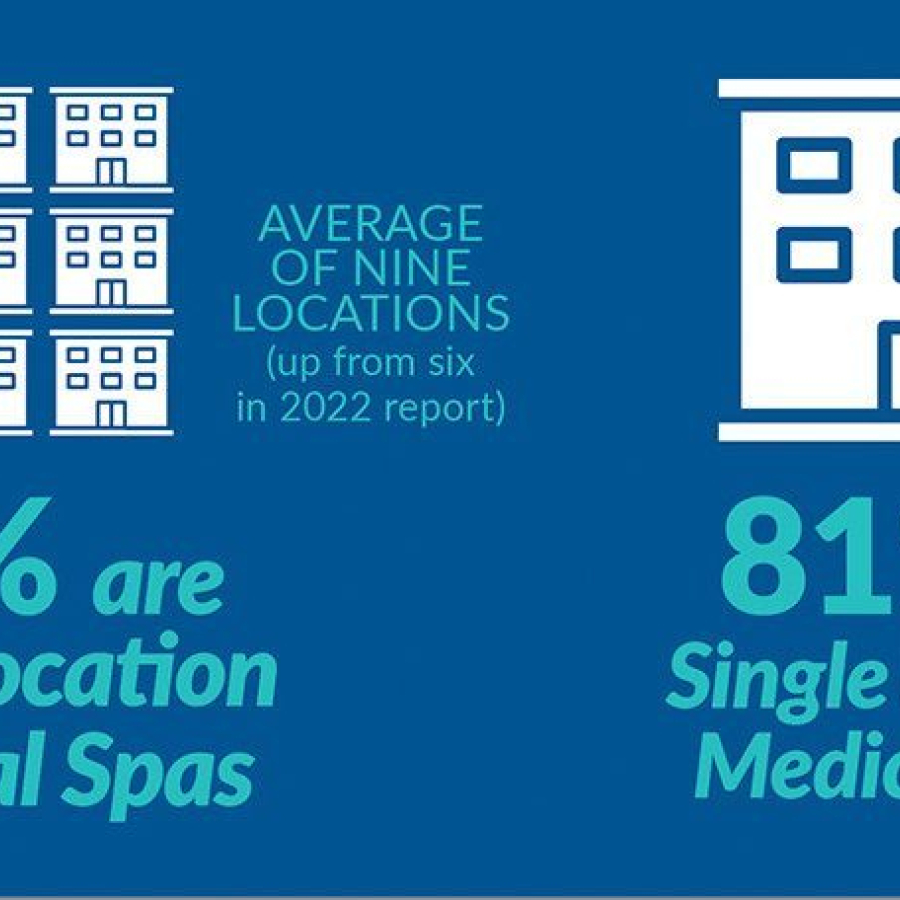

By Michael Meyer Approximately every two years, the American Med Spa Association (AmSpa) releases its Medical Spa State of ...

Trends

By Michael Meyer Since the beginning of 2024, it seems like medical aesthetics has taken one hit after another ...